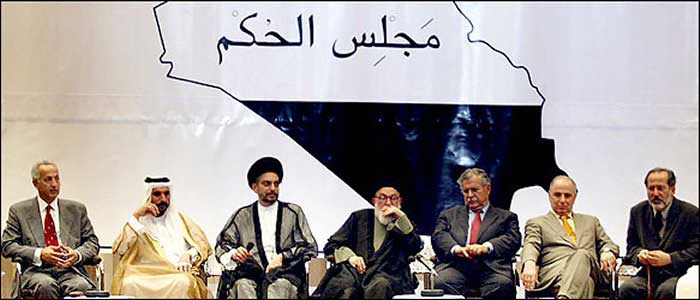

Members of the new Iraqi Governing Council in Baghdad on Sunday, with the panel's name in the background. BAGHDAD, Iraq, July 13 — Three months after the fall of Saddam Hussein, 25 prominent Iraqis from a variety of political, ethnic and religious backgrounds stepped onto a stage here today and declared themselves the first interim government of Iraq. The members of the Governing Council said they would begin meeting in continuous session on Monday to decide on a rotating presidency or a similar leadership structure. As its first act today, the Council abolished six national holidays that had been celebrated under Mr. Hussein's 24-year rule and created a new national day. Two of the banned holidays were fast approaching, adding to the urgency of forming a government, Iraqis said. Monday, July 14, is the anniversary of the 1958 overthrow of the monarchy, and July 17 is the anniversary of the 1968 coup that brought Mr. Hussein's Baath Party to power. In their place, the Council declared April

9, the day that Baghdad fell to allied forces as Mr. Hussein went into

hiding, the national day of a new Iraqi state. That state will not emerge

until the interim government decides on a process to write a new constitution

and to hold the first democratic elections. No timetable for either task

has been set.

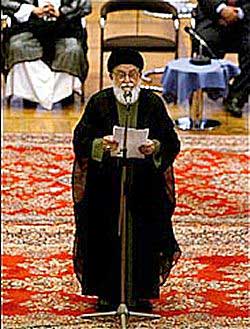

When the 25 emerged for a news conference, 2 wore the black turbans of Shiite Islamic clerics descended from the Prophet Muhammad and 2 wore the flowing robes and headdresses of tribal sheiks. Three women were among them, two in head scarves and one without. The rest, men of various political stripes, wore business suits. They arranged themselves in a semicircle as one of the clerics, Sayyed Muhammad Bahr al-Uloum, read a one-page statement, saying, "The establishment of this Council is an expression of the national Iraqi will in the wake of the collapse of the former oppressive regime." The occupation leaders looked up at them from the front row in the convention center hall. During weeks of negotiations, they agreed to cede considerable executive powers to Iraqis after initially resisting anything greater than an advisory role. They did so in the face of a daunting reconstruction agenda, a critical shortage of money and a security environment that resembles a low-intensity war for the more than 160,000 allied troops. From here forward, the 25 Iraqis — doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, clerics, diplomats, political activists, businessmen and a judge — will share responsibility for the course of postwar Iraq. A Kurd, Hoshyar Zebari, the political adviser to Massoud Barzani, leader of the largest Kurdish political party, was designated as the Council's press secretary. But when they walked out on stage, it was the elderly cleric, Mr. Uloum, who approached the microphone. Holding the text of the statement just below his snowy white beard and squinting through thick glasses, he intoned, "In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate." Establishing this interim government is the first significant political milestone in postwar Iraq, and some of the new government members expressed a strong determination to expand their powers. "We hope that this Council will work for a very short time," said Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, the other Shiite cleric who represents the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution of Iraq. "We should have a constitutional government and we should get rid of the occupation." The very diversity of such a large Council raised questions of whether it would be able to project unified goals and principles in a chaotic transitional period where significant segments of the population were pulling in different directions. In the north, Kurds are seeking to protect the autonomy they have won over the last 12 years. In the center, Sunnis are divided by mistrust for Western occupation and old loyalties to Mr. Hussein. In the south, Shiites worry that their majority status will be subordinated, as it was in the last century, to the Sunni minority. Members of the Council said today that they had been assured that their decisions would not be vetoed by the occupation authority. "I don't foresee that Mr. Bremer will ever cast a veto against any decision taken by the Council," said Adnan Pachachi, 80, a foreign minister and ambassador to the United Nations during the pre-Hussein era of the 1960's. "We were assured that all decisions of the Council will be respected." Differences of opinion, he added, can "be managed easily through consultation." Mr. Bremer was urged by a number of advisers to lower his profile so as to underscore the Council's independence. He has withdrawn significantly from asserting any role in organizing the task of writing a constitution. The Council will set up a preparatory committee to decide the process for selecting a drafting committee. Great difficulties surround the constitutional question. Earlier this month, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, one of the leading clerics of Shiite Islam, warned that the occupation powers should have no role in the constitutional process. A number of the council members said they would work to devise a selection process that would win the acceptance of the grand ayatollah, who has yet to meet with any official from the occupation powers. The only non-Iraqi to speak at the ceremony was Mr. Vieira de Mello. "Iraq today finds itself in a unique and difficult situation: a great country beset by much recent tragedy, currently without full enjoyment of its sovereignty," he said. "Today, therefore, your convening marks the first major development towards the restoration of Iraq's rightful status as a fully sovereign state." The liveliest moments of the news conference occurred when some council members disputed questions from the news media. The Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani criticized a BBC correspondent for suggesting that the interim government would have limited powers and therefore little legitimacy among the Iraqis. "The Council has a lot of authority, appointing ministers, diplomats, budgets, security," Mr. Talabani said. He then accused the BBC of having been biased toward Mr. Hussein's government during the war. The strongest comments were directed at the Arab satellite channel Al Jazeera. "The satellite channels are expecting Saddam to come back, but he is in the trash can of history," Mr. Uloum shouted after someone else questioned the legitimacy of the interim government. "I am very sorry these Arab channels betrayed their Arab brothers." Only one of the council members, Ahmad Chalabi of the Iraqi National Congress, expressed public gratitude to the United States and Britain for removing the former government. A majority of the council members are drawn from the ranks of Iraqi opposition leaders in exile and Kurdish leaders from northern Iraq, who led the external fight to topple Mr. Hussein. One Iraqi who carried on that struggle from inside Iraq, Abdul Karim Mahoud, said today, "Those who were outside of Iraq represent some Iraqi opposition groups, and we hope now that they're back in Iraq they will represent some of the Iraqis in this country."

|