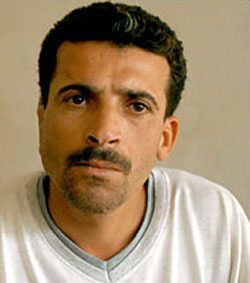

He now has a walleyed stare to show for eight years in prison. He is quick to pop out his glass eye for a visitor — and to tell of how he lost the real one to torture. Farris Salman is one of the last victims of Mr. Hussein's rule. His speech is slurred because he is missing part of his tongue. Black-hooded paramilitary troops, the Fedayeen Saddam, run by Mr. Hussein's eldest son, Uday, pulled it out of his mouth with pliers last month, he said, and sliced it off with a box cutter. They made his family and dozens of his neighbors watch. "I thought they were going to execute me," said Mr. Salman, sitting on the floor in his family's small house in a run-down neighborhood of the capital a week after being freed by a frightened prison warden as Americans took control of the city. "When one of the fedayeen said they were going to cut my tongue out, I said, `No, please, just kill me.' " The tales of torture burn fresh in the memory, regardless of how many years have passed since the damage was done. Mr. Datajji said he was detained for questioning after the country's 1991 Shiite uprising. In 1994, the secret police kicked in his door and rounded up the 14 males in his extended family. All were eventually released — except for Mr. Datajji and a 24-year-old nephew. The nephew was hanged after eight months in jail. Mr. Datajji spent over two years in a lightless, six-foot-square cell from which he was summoned for what he said were countless sessions of torture. Sometimes they hung him by his arms from behind, pulling his shoulders out of joint. Sometimes they beat him with a thick wooden club and sometimes jolted him with electricity. Sometimes, he said, they did all three. One day, they pulled out four of his toenails. "At the beginning, I was afraid, but it became normal," he said. "Of course you scream, but it is normal to scream." Some people died; he does not know why he survived. "I can't even imagine it now," he said. "It's something like watching a video for me." After two and a half years, he was sentenced to 15 years for sedition and moved to Baghdad's Abu Ghraib prison, sharing a 15-foot square cell with 30 to 40 other prisoners. When cellmates fought, he said, everyone was punished with more torture. After a few years, his right eye became swollen from so many beatings. A doctor in the prison hospital promised an operation. "I thought they were going to fix my eye," he said, "but when I woke up I had just one eye left. They had cut the other one out." Mr. Datajji was suddenly released last October as part of a general pardon declared by Mr. Hussein. He said many of the people in his cell had become insane by then, and a few did not want to leave. After he returned home, he was still required to report to the local intelligence bureau once a week. The last time he went there was two days before the war started. "I don't know where they are now," he said, and laughed for the first time in two hours. "They have all vanished." Mr. Ghanem was drafted just after Iraq was defeated by the United States in the Persian Gulf war in 1991. He deserted once, in 1992, and lived on the run before returning to the army in 1994 when Mr. Hussein offered amnesty to deserters. After he left again for a week to help his widowed mother, he was told that Mr. Hussein had ordered one ear lopped off all conscripts who left their units. Doctors gave him an injection and he lost consciousness, he said. When he awoke, the right side of his head was wrapped in bandages. It was Sept. 15, 1994. "I started crying," Mr. Ghanem said. "I felt crippled. I felt oppressed. I hated Saddam with all of my heart, but I didn't know what to do." He was sent to prison where he said he saw hundreds of others missing one ear. Many, like Mr. Ghanem, had inflamed wounds. His mother came every Friday, selling off household appliances to buy painkillers and antibiotics for her son. Others were less fortunate. Mr. Ghanem described a medieval scene in which delirious and dying inmates lay on the prison's dirt floor screaming from pain. "The right side of some of the men's heads were puffed up like red balloons," he said. Two of his friends died from infections. Many inmates had tuberculosis, Mr. Ghanem said, and when he developed a cough in 1996 he was sent under guard to a hospital. He managed to slip into a crowd, and ran away once more. In 1999, Mr. Hussein offered deserters amnesty again. Mr. Ghanem returned to the army, and was sent to the Jordanian border. As war with the United States drew near this spring, he said his unit was ordered to fire on Iraqi civilians trying to flee to Jordan. When the war began, his unit simply dissolved and he went home again, this time, he hoped, for good. "Saddam, God curse him, treated my son like an animal," said Mr. Ghanem's weeping mother. "Only animals have their ears cut off." A doctor for the fedayeen confirmed that maiming was a common form of punishment under Mr. Hussein. He said that some soldiers had their ears cut off or their limbs broken. Mr. Salman said blurrily that his offense was cursing Mr. Hussein last December, after a brawl with a local intelligence officer who had taken away two of Mr. Salman's uncles after a Shiite uprising in 1991. Mr. Salman, 23, and another uncle had gone to seek information about the missing men, he said. After the brawl, which ended with a fedayeen member shooting in the air, he and his uncle fled, but returned home after 10 days on hearing a false rumor that it was safe to do so. Mr. Salman and three of his uncles were arrested within hours. For two months, he said, the men were repeatedly tortured at a prison in the Zaiona district of the capital. Then, on March 5, Mr. Salman was blindfolded and bundled into a van. Residents of his neighborhood say the van arrived in the afternoon with an escort of seven trucks carrying more than a hundred black-uniformed fedayeen wearing black masks that only showed their eyes. They rounded up neighbors for what was billed as a rally; Mr. Salman's mother was ordered to bring a picture of Mr. Hussein. Two men held Mr. Salman's arms and head steady, and pointed a gun to his temple. Another man with a video camera recorded the scene. "I was standing and they told me to stick my tongue out or they would shoot me, and so I did," Mr. Salman said. "It was too quick to be painful but there was a lot of blood." The fedayeen stuffed his mouth with cotton and took him to a local hospital, where he got five stitches, no painkiller and was returned to prison. Moaed Hassan, the owner of the tea shop outside of which the deed was done, said the fedayeen officer who cut the tongue held it up to the crowd and shouted, "You see this? This will be the fate of anyone who dares insult the president." He then threw the bit of flesh on the ground; another fedayeen officer scooped it up and said it would be given to Uday Hussein as a present. Ten days later, after the Americans started bombing, Mr. Salman and inmates of the Zaiona prison began an odyssey around other Baghdad detention places. Eventually, last week, a frightened prison warden stopped a truck during yet another transfer, and announced he was releasing his captives. As a final gesture, the warden insisted the prisoners clap and chant, "We sacrifice our blood and soul for Saddam." Then the guards left. Mr. Salman and one of his uncles flagged down a car, which took them home.

|