| Shortly after the U.S. military

campaign in Afghanistan began last October, Khan joined forces with the

Northern Alliance, which drove the Taliban and al-Qaida forces from Herat.

And although he currently

holds no official title under the interim government headed by Hamid Karzai,

his grip on this strategically crucial city is unquestionable.

Not even a single passport

can be processed without the personal authorization of the warlord himself,

one resident said.

But Khan’s reign has brought

a ray of hope to Herat. Like other cities throughout Afghanistan, the Taliban’s

extreme form of Islam has been banished: Girls are back at school, men

need not wear long beards and there is music in the streets.

But there remains dire poverty

and a great deal of political intrigue.

RENEWED RIVALRIES

On Tuesday, the commander

of Afghanistan’s international security force held talks with Khan after

rival warlords threatened to march on the city.

Britain’s Gen. John McColl,

head of the International Security Assistance Force, had breakfast with

Khan in a mansion next to a military base on the ancient city’s outskirts.

Khan’s foreign affairs spokesman,

Mohammad Ullah Affali, said the talks between McColl and Khan were likely

to cover the possibility of international troops being based in Herat.

“We are discussing

the situation. I don’t think there will be a problem. Maybe there will

be a need, maybe not,” he told Reuters. |

|

Reports of Iran supplying

weapons to forces in Herat have raised consternation in neighboring provinces.

The governor of Kandahar,

Gul Agha Shirzai, threatened to march 20,000 fighters to Herat to rid southwestern

Afghanistan of soldiers equipped by Iran.

Shirzai claimed that the

soldiers were preying on ethnic Pashtuns in trucks carrying his trade convoys,

raising fears of internecine fighting.

But Iran has vehemently denied

accusations of meddling in Afghan affairs. During U.N. Secretary General

Kofi Annan’s recent visit to Tehran, officials denied they were arming

any of the factions inside Afghanistan. Iran also declared full support

for Karzai’s government.

But suspicions remain. On

the main road connecting Iran and Afghanistan, numerous trucks with Iranian

plates roll by, making their way deep into Herat and beyond. And the presence

of a functioning Iranian consulate in the city center is a strong reminder

of the close relations between Tehran and Herat.

FLORENCE OF ASIA

The largest city in western

Afghanistan with an estimated population of 140,000, Herat is about 500

miles from Kabul.

It’s through its proximity

to Iran, only 75 miles away, that Herat gained a reputation as a commercial

and cultural crossroads in the region.

The city dates to the days

of Alexander the Great, who began construction of a magnificent citadel

here. The golden age of Herat was in the 14th and 15th centuries, when

the city was known as the Florence of Asia. The past splendor is still

obvious when you visit the city’s mosque, a breathtaking piece of architecture

with its fine tiles and marble foundation.

But Herat’s glory has mostly

faded. As in the rest of the country, most intellectuals with means to

escape have long left the city.

A dusty city locked in time,

mud huts and shacks line Herat’s streets, while horse-drawn carriages and

men riding on mules zigzag between rundown buses and overloaded trucks

down bumpy, pot-holed boulevards.

Alexander’s once grand citadel

is surrounded by half collapsing mud huts, and just outside its walls,

local people have turned one of its vantage points into a public latrine.

Nearby is Maslakh camp, home

to more than 180,000 Afghans who have taken refuge from a deadly three-year

drought that has left most of Afghanistan without crops and food.

According to aid workers,

this is the world’s largest camp for internally displaced people. Even

today, desperately hungry Afghans arrive at this camp daily.

“Nobody wants to move from

the camp. They know there is food and security here,” said Alejandro Chicheri

of the World Food Program.

At the sprawling complex

of mud houses and tents, there is at least enough food for the people to

stay alive. But it’s not the plight of these hungry refugees that draws

the attention of the world.

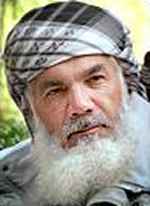

AN AUDIENCE WITH KHAN

NBC was recently summoned

to Khan’s office for a late-night news conference along with a dozen other

foreign journalists.

As he sat as his desk, journalists

bided their time while a group of men sought his signature on various permits

and documents.

Two elderly scribes sat at

the back of the room, pen and paper at the ready, to jot down every word

their master would utter during the news conference, where the media focused

on his ties with Iran.

“We’ve always had friendly

ties with Iran, a country which has supported Afghanistan through its war

against the Soviet occupation and the Taliban,” Khan said through his interpreter.

“Over 2 million of our people are refugees there, and some of our commanders

still have their wives and children living in Iran. So it is natural for

us to have close relations with them. But there is no military assistance

coming our way from Iran.”

Different versions of the

same question were posed over and over again, but the warlord’s reply was

consistent.

After the news conference

wrapped up, the media convoy was escorted by Khan’s officials as it was

past the 10 p.m. curfew in Herat. Along the pitch-black street, well-disciplined

and business-like soldiers loyal to Khan manned several checkpoints.

Even in the darkness, their

brand-new green fatigues and polished guns were visible, raising the

obvious question of who’s

financing Khan’s force in this impoverished city.

|